The childcare crisis in the U.S. is a complex issue with far-reaching personal and economic consequences. On the demand side, it’s often difficult for families to both find quality childcare and afford it. The average annual cost for childcare is typically between $12,000 and up to $24,000, depending on the region. On the supply side, even before the pandemic there was a shortage of childcare workers; and today, there are roughly 100,000 fewer childcare workers than there was pre-pandemic.

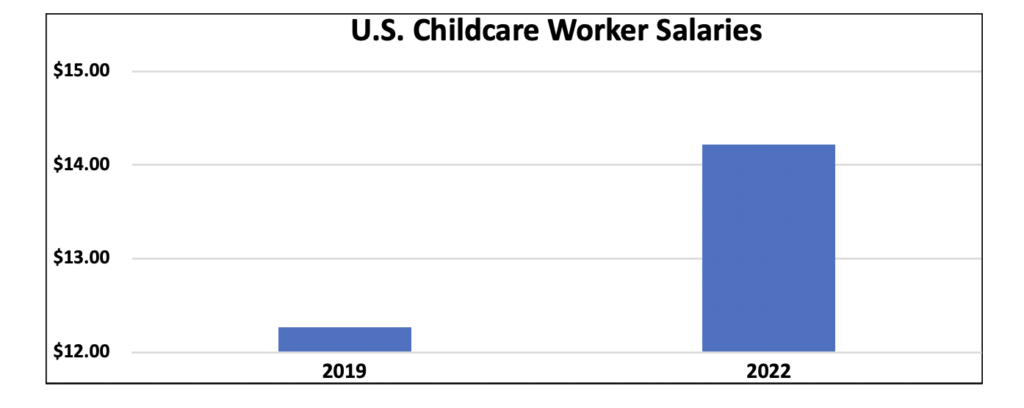

And now we have another headwind. The American Rescue Plan, one of the pandemic emergency programs, provided $24 billion in subsidies to childcare centers that suddenly had an even more acute shortage of workers. With the reality of fewer working-age people in the United States, many of those former childcare workers found easier office or remote work that usually paid better (see chart), and often with benefits. Owners of childcare centers had to raise wages to compete and most of the $24 billion was used to help cover those expenses. This kept a lot of childcare centers operational.

But that funding expires on September 30. More than 70,000 childcare programs are expected to close across the U.S., and 3 million childcare slots will disappear. In Colorado, 83,000 children will lose their childcare slots according to The Century Foundation and research by Catherine Rampell. We have the additional challenge of student loan payments resuming in October. What about young families who must work, pay hefty student loan payments, and also pay for childcare? What hasn’t been working well is about to get worse.

I think back to when my five kids were young and how my husband and I made the decision for me to work part-time and mostly from home, which was definitely a privilege (not to mention the best and most meaningful years of my life). But I also have a lot of education, yet the math didn’t work for us to pay for childcare – even for one child. The math doesn’t work at an aggregate national level either.

If we look at specific local data, in 2022 the median annual household income in Colorado Springs was $82,389, according to the Census Bureau. At this median income, for a family of four with two children under the age of three, childcare for those children would be approximately $25,000 per year, according to local estimates. This would be with a $15,000 income-based subsidy at facilities that participate in such programs. Without this $15,000 subsidy, the full tuition for two children under age three in Colorado Springs is estimated to be $40,000 per year. And let’s remember that household incomes are in gross dollars (e.g., before taxes). If a household has an income of $100,000 at a 28% tax rate, their take-home pay is $72,000 a year, but they may or may not qualify for subsidies, depending on the facility and the specifics of any sliding scale subsidies. If a family cannot find a childcare facility with subsidies, for a household income of $100,000, childcare for two children under three would take up more than half of their take-home pay.

For a young family, this is simply not doable. As a result, fewer young people are forming families. We need not look further than Japan to see the economic consequences of low birthrates alongside significantly longer life spans. We already have a tight workforce market due to the bust of the baby boom and declining birth rates that started decades ago. Even lower U.S. birth rates today will amplify the workforce shortage. To be sure, there are negative externalities to an overcrowded planet. But for those who want children and want to work outside the home, it shouldn’t be this difficult. Families should be able to be at “replacement fertility” of roughly two children per family, if they so desire. As it stands right now, childcare is one instance where I think society would benefit from both public and private subsidies.

A few years ago, my office did a return-on-investment analysis for subsidized early childhood education for four year olds, funded by the Legacy Institute. In the short run, for every dollar put into the program, the government gets back $1.20 because more parents can work and pay taxes, and there is a reduction in federal assistance programs like food stamps. Over the long run, child outcomes are better and the return-on-investment increases to $1.30 – or put another way, a 30% return – a healthy return by any standards. These are not handouts, but sound financial investments that pay for themselves, increase our global competitiveness, and help families work and thrive.

Tatiana Bailey is executive director of the nonprofit Data-Driven Economic Strategies (DDES). Thank you to Gaby Glassford for research support, and thank you to Early Connections for their contributions and hard work in this realm. An abridged video with this information recently aired on The Economic Update with Tatiana Bailey on Fox21 and can be found on their website or at ddestrategies.org. The abridged article was published in The Gazette on August 31, 2023.